Richland County Park District

Current Issues

Richland County Park District

Current Issues

Richland County Park District

Current Issues

Richland County Park District

Current Issues

This is not an exhaustive list of current issues. For more information visit the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) or the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA).

What Is an Emerald Ash Borer?

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis or EAB) is an insect from Asia that was first identified in Ohio in 2003, and which is lethal to ash trees. The pest has since spread from its initial detection site near Toledo to all of the counties in the state. Because the EAB has established itself throughout all of Ohio, the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA) has lifted the state EAB quarantine regulations as of July 2011. Ohio is still inside the Federal quarantine boundary, and the movement of EAB regulated articles cannot exit quarantine boundaries without Federal permits.

Emerald Ash Borer Background

The EAB is a small but destructive exotic beetle from Asia. It was first discovered in July 2002 feeding on ash trees in southeastern Michigan, likely arriving in wooden packing material at a harbor near Detroit. Evidence suggests that EAB had been established in Michigan for at least ten years. More than 3,000 square miles in southeastern Michigan are infested and more than 6 million ash trees are dead or dying from this pest.

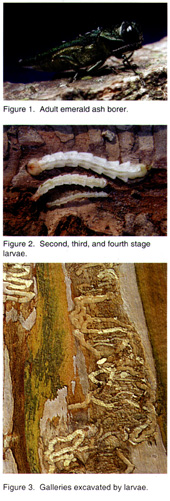

Metallic green in color, EAB adults measure 1/2 inch in length and 1/8 inch wide. The average adult beetle can easily fit on a penny. Adult beetles lay eggs in the bark of any ash species (White, Green, Black, Blue), and after hatching, larvae feed in the cambium between the bark and wood. Larval feeding results in galleries that eventually girdle and kill branches and entire trees.

EAB was identified in Ohio in February 2003. Since then, it has moved progressively across the state, and on October 3, 2006, the ODA confirmed the presence of EAB in Cuyahoga County. Subsequently, the ODA placed the county under EAB quarantine, prohibiting the movement of harvested ash wood products, including firewood, from quarantined counties into non-quarantined counties. The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services (APHIS) Emerald Ash Borer webpage contains up to date information and distribution maps concerning EAB in Ohio and across the US. For an international perspective on EAB, click here for information and links to many other web sites concerning this destructive pest.

Firewood Alert

The key factor contributing to the spread of EAB is the movement of infested firewood. Firewood, tree trimmings, and other debris may not be brought into or dumped at Richland County Park District Properties under any circumstances.

Many people unknowingly contribute to the spread of EAB when they move firewood, so don't move firewood. EAB larvae survive hidden under the bark of firewood. Play it safe: if you don't move any firewood, you won't move any beetles. Since early detection is a key factor, visually inspect your trees. If trees on your property display any signs or symptoms of EAB infestation, contact your state agriculture agency.

RCPD Internal Policies Regarding EAB (Effective Since 2015)

Internal policies provide guidelines for park managers to slow the spread of Emerald Ash Borer and remove infested ash trees from public facility and recreation sites while continuing the Richland County Park District's mission of natural resource conservation.

Park district staff will inspect ash trees for signs of EAB infestation during routine tree maintenance, including pruning, dead-wooding and removal. Any signs of emerald ash borer will be immediately reported to the Natural Resource Division and further work on the infested tree/trees will cease immediately until the scope of the infestation is investigated.

Ash trees either pruned or felled (including storm damaged trees) will be hauled to a pre-designated holding area in the park where the tree was located. Park district staff will process accumulated ash wood into wood chips less than 1" by 1" and compost them.

If ash trees or tree pieces cannot be stored in a holding yard, they will be cut into pieces longer than 6 feet and scattered in the forest adjacent to where the tree was located for a minimum of 2 full (fall through summer) seasons before being pieced for firewood if necessary either for aesthetics or debris control. Workers will chip as much of the non-trunk portion of the ash debris as possible.

What Is Beech Leaf Disease?

Beech leaf disease (BLD) is a lethal disease afflicting our native American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) trees as well as several non-native beech trees, including European Beech (Fagus sylvatica) and Oriental Beech (Fagus orientalis). BLD was first discovered by Biologist John Pogacnik in Lake County in 2012. To date, BLD infestations have been discovered in at least a dozen Ohio counties as well as in localized areas across Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario, Canada. BLD is believed to be caused by a nematode subspecies called Litylenchus crenatae mccannii. The ODNR Division of Forestry has received funding from the US Forest Service to work with various partners across the US and Canada to monitor the spread and document the impact of BLD, helping to inform research efforts and create management tools.

What Are Symptoms of BLD?

Symptoms of BLD include dark striping or banding on otherwise healthy-looking leaves, shriveled, discolored, or deformed leaves, and reduced leaf and bud production. Once infected, leaves opening in the spring will immediately show dark banding. Stripes are still visible on remaining leaves in the winter. Disease progression varies with tree size, but BLD appears to kill small trees within several years. No infected tree has ever been known to recover. BLD is not to be confused with beech blight aphids or eriophyid mites.

Click here for more information regarding BLD.

How Do I Report BLD?

ODNR urges Ohioans to report BLD. Reports of BLD will be documented to inform future research and to monitor changes in forest composition and structure. Landowners in northeast Ohio are encouraged to report any signs of BLD and report healthy beech trees. Additionally, landowners are urged to avoid moving beech trees or tree parts to prevent BLD from potentially spreading to new areas.

To report BLD, contact ODNR Forest Health Program Administrator Tom Macy at thomas.macy@dnr.ohio.gov or use the BLD section of the NE Ohio Parks app.

What Is an Asian Longhorned Beetle?

The Asian Longhorned Beetle (ALB) is an exotic invasive wood-borer beetle in the family Cerambycidae that feeds on a wide variety of trees encompassing 12 genera in 9 plant families, with maples (Acer spp.) being the most ecologically and economically significant in the United States, eventually killing them. The beetle is native to China and the Korean peninsula and was most likely brought to the United States in wood packing material such as crates or pallets. Adult beetles are large, distinctive-looking insects measuring 1 to 1.5 inches in length with long antennae. Their bodies are black with small white spots, and their antennae are banded in black and white. Checking your trees regularly for this insect, looking for the damage it causes, and reporting any sightings can help prevent the spread of the beetle. If not eradicated, ALB poses a severe threat to North America's natural and urban forests.

History of ALB in the United States

First detected in North America in 1996 in New York City, additional infestations have since been found in New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Ontario, Canada. The beetle has been successfully eradicated in Illinois, New Jersey, and parts of New York and Ontario. Eradication efforts continue in other states and Ontario where ALB has been found.

Ohio was the fifth state to find ALB. In Ohio, ALB was discovered in Tate Township in Clermont County in June 2011, and the Ohio ALB Cooperative Eradication Program was established with the goal of eradicating the infestation. Participating agencies include the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA), the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), the Ohio State University Extension, the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service and the USDA Forest Service. Quarantines were established in Clermont County to prevent the spread of ALB. The removal of regulated items that could spread the beetle, such as logs, trees, tree trimmings, chipped wood with pieces larger than 1 inch in two dimensions, and firewood, from the quarantined area is restricted by law. This invasive beetle has no known natural predators and poses a threat to Ohio's hardwood forests (more than $2.5 billion in standing maple timber) as well as the state's $5 billion nursery industry, which employs nearly 240,000 people.

What Is ALB's Host Range?

ALB has a broad host range that includes trees representing multiple species from 12 genera: maples (Acer spp.); horse chestnuts and buckeyes (Aesculus spp.); elms (Ulmus spp.); willows (Salix spp.); birches (Betula spp.); sycamore and planetrees (Platanus spp.); poplars (Populus spp.); mimosa (Albizia julibrissin); katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum); ash (Fraxinus spp.); golden raintree (Koelreuteria paniculata); and mountainash (Sorbus spp.).

What Is the Life History of ALB?

Adult females chew depressions known as "oviposition pits" into the bark of various hardwood tree species. They lay an egg about the size of a rice grain under the bark at each site. Females can lay up to 90 eggs in their lifetime. Within 2 weeks, the egg hatches and the white larva bores into the tree, feeding on the living tissue (xylem & phloem) that carries nutrients and the layer responsible for new growth under the bark. After several weeks, the larva tunnels into the woody tree tissue, where it continues to feed and develop over the winter. Larvae molt and can go through as many as 13 growth phases. As the larvae feed, they form tunnels or galleries in tree trunks and branches. Sawdust-like material, called frass, from the insect’s burrowing can be found at the trunk and branch bases of infested trees.

Feeding by ALB larvae damages the xylem, which moves water from the roots to the canopy of the tree. As larval feeding continues over time, damage to the xylem slowly accumulates, causing structural weakening in tree branches. Branches often break, especially during storms. Eventually, larval feeding kills the tree. The larvae typically feed through the summer and fall until pupation, but occasionally, pupation occurs in the spring.

Over the course of a year, beetle larvae develop into adults. The pupal stage lasts 13 to 24 days. Adults emerge in late spring through late summer with peak emergence typically occurring in late June to early August; however, adults can be present in the fall. Mating begins 2 to 3 days after emergence. ALB can overwinter in the egg, larval or pupal stage, but adults do not survive the winter, dying after the first fall freeze. There is one generation per year. After adult beetles emerge from the pupae, they chew their way out of the tree, leaving round exit holes approximately three-eighths of an inch in diameter. Once they have exited a tree, they feed on its leaves and bark for 10 to 14 days before mating and laying eggs.

Because ALB can overwinter in multiple life stages, adults emerge at different times. This results in their feeding, mating, and laying eggs throughout the summer and fall. While adult beetle activity is most obvious during the summer and early fall, adults have been seen from April to December. Adult beetles can fly for 400 yards or more to search for a host tree or mate. However, they usually remain on the tree from which they emerged, resulting in infestation by future generations.

Signs of ALB start to show about 3 to 4 years after infestation, with tree death occurring in 10 to 15 years depending on the tree’s overall health and site conditions. Infested trees do not recover, nor do they regenerate. Foresters have observed ALB-related tree deaths in every affected state.

Prevent the Spread

ALB has the potential to become a catastrophic pest of hardwood trees in North America due to a wide range of suitable hosts and difficulties in detection and monitoring. If the spread of this beetle is not stopped, ALB will cause significant ecological and economic impacts. The forest products and nursery industry in Ohio and elsewhere would be threatened by the loss of trees. Tree mortality caused by ALB will also impact biodiversity and ecosystem services in urban and natural forests. The eastern and southern half of Ohio is dominated by hardwood forests, and damage to trees will impact homeowners, parks and recreation, and maple syrup processors. Additionally, the state tree of Ohio, the buckeye, is a host for ALB.

Eradication efforts in some areas of North America have been successful, and those efforts continue in Ohio. However, if ALB is allowed to spread, those efforts will be undermined. To prevent the spread of ALB, quarantines are established in areas where the beetle has been detected. Removing infested trees or high risk host trees in the surrounding area is essential to stop the spread of ALB and save millions of trees. Do not transport living or dead trees, including firewood, branches, roots, stumps, or other debris from quarantined areas. Larvae often go unnoticed because feeding occurs under the bark, and this is why transporting wood is a major problem. It is particularly important to purchase firewood where you plan to burn it to avoid spreading ALB or other pests, such as Emerald Ash Borer, Gypsy Moth, and Walnut Twig Beetle.

Early detection of ALB infestations is critical to the success of eradication efforts in terms of time and money. Most infestations have been identified by alert citizens that find the beetle, but careful monitoring for tree damage will also help catch an infestation early. If signs or symptoms of ALB are found, report the infestation to the Ohio Department of Agriculture by phone at (614) 728-6201 or online at agri.ohio.gov. Citizens in Ohio or other states may also report a suspected ALB infestation to USDA APHIS by accessing their ALB website and clicking on “Have You Seen The Beetle” at asianlonghornedbeetle.com.

What Is a Tick?

Ticks are blood-feeding parasites that can pose a serious health risk to pets and humans impacting quality of life. Ticks have the ability to infect their hosts with a number of tick-borne diseases that can cause mild to severe illness or death. Proper tick bite prevention measures and removal techniques are the best way to avoid infection.

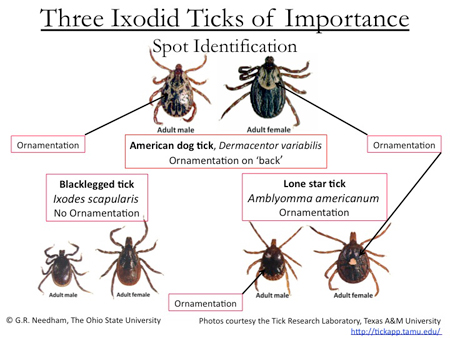

Richland County has three tick species of medical significance because they are disease vectors: Blacklegged Tick (often called the deer tick), American Dog Tick, and the Lone Star Tick. All three species are known as hard ticks because they possess a scutum (hard plate) on their upper surface behind their mouth parts. The scutum nearly covers the entire upper surface of male ticks and the front portion of the upper surface of female ticks. Soft ticks lack a scutum and are not pests to humans in Ohio.

Tick Life Cycles and Habits

Ticks have a life cycle that includes the egg and three stages: six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and eight-legged adult. Adult ticks often have distinct characteristics and markings, but immature stages (larvae and nymphs) are entirely tan or brown and difficult to identify to species. All stages are round to oval shaped.

Ticks must consume blood at every stage to develop. Most species feed on a different type of host during the adult stage, with larvae and nymphs preferring smaller hosts. Nymphs become engorged, but they are much smaller than the adults. Adult female ticks greatly increase in size during feeding but adult males do not.

Important Tick Species in Ohio

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

The American Dog Tick is the most commonly encountered species throughout Ohio.

Identification: Adults are typically brownish with light gray mottling on the scutum. Immatures are very small and rarely observed. The adult American Dog Tick is the largest tick in Ohio at approximately 3/16 of an inch (unfed females, fed and unfed males). After feeding, the female is much larger (about 5/8 of an inch long) and mostly gray.

Biology: American Dog Ticks prefer grassy areas along roads and paths, particularly next to woody or shrubby habitats. The immature stages of this species feed on rodents and other small mammals. Adult ticks feed on a wide variety of medium to large size mammals such as opossums, raccoons, groundhogs, dogs, and humans. Adults are most commonly encountered by humans and pets.

Adults are active during spring and summer, but they are most abundant from mid-April to mid-July. The adult tick waits on grass and weeds for a suitable host to brush against the vegetation. It then clings to the host’s fur or clothing and crawls upward seeking a place to attach and feed. Attached American Dog Ticks are frequently found on the scalp and hairline at the back of the neck.

Males obtain a small blood meal then mate with the female while she is attached to the host. The female feeds for seven to 11 days then drops to the ground and remains there for several days before laying approximately 6,000 eggs then dying shortly thereafter. The male remains on the host and continues to feed and mate for the remainder of the season until his death.

Diseases: The American Dog Tick is the primary transmitter of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF). This species may also transmit tularemia. Toxins in the tick's injected saliva have been known to cause tick paralysis in dogs and humans. Immediate tick removal usually results in a quick recovery.

Blacklegged Tick or Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis)

The Blacklegged Tick has recently emerged as a serious pest in Ohio. This species has become much more common in the state since 2010, particularly in regions with the tick’s favored forest habitat. Maps showing Ohio counties with the Blacklegged Tick are available on the Ohio Department of Health's Tickborne Diseases website.

Identification: The larval stage of the Blacklegged Tick is extremely tiny and nearly translucent, which makes it extremely difficult to see. The nymphal stage is translucent to slightly gray or brown. Adult males are slightly more than 1/16 of an inch long; unfed females are larger (about 3/32 of an inch long). Both sexes are dark chocolate brown, but the rear half of the adult female is red or orange. Engorged adult females may appear gray. All comparable stages of the Blacklegged Tick are relatively smaller than other medically important ticks.

Biology: Blacklegged Ticks are found mostly in or near forested areas. The immature stages feed on a wide range of hosts that occur in their woodland habitats. Adult Blacklegged Ticks feed on large mammals, most commonly white-tailed deer. Hence, some people call them "deer ticks." Mating can occur on or off of a host. The female deposits approximately 2,000 eggs, all in one location.

All stages may attach to humans. They have no site attachment preference and will attach almost immediately upon encountering bare human skin.

One or more life stages may be active during every month of the year, depending on temperature. Because of this year-long activity, preventative measures should be taken outdoors where the tick occurs, even during autumn and winter.

Diseases: The Blacklegged Tick is the only vector of Lyme Disease in the eastern and midwestern United States. It is also the principal vector of human granulocytic anaplasmosis and babesiosis. This tick species may be co-infected with several disease agents, and some ticks may simultaneously infect a host with two or more of these diseases.

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Lone Star Ticks have recently emerged as a serious pest, especially in southern Ohio.

Identification: The unfed adult female is about 3/16 of an inch long, brown, with a distinctive silvery spot on the upper surface of the scutum (hence the name "lone star"). Once fed, the female is almost circular in shape and about 7/16 of an inch long. The male tick is about 3/16 of an inch long, brown, with whitish markings along the rear edge.

Biology: Lone Star Ticks are most commonly found in southern Ohio, but they are dispersed by migratory birds and therefore are reported in most Ohio counties. All stages readily feed on almost any bird or mammal, including humans. All stages can be found throughout the warm months of the year.

Shade is an important environmental factor for this species, typically occuring in less sunny locations along roadsides and meadows and in grassy and shrubby habitats. All stages crawl to the tip of low growing vegetation and wait for a host to pass by. Larval Lone Star Ticks, commonly referred to as seed ticks, may congregate in large numbers on vegetation. A person or pet unlucky enough to brush against this vegetation may become host to hundreds of larval ticks. The sticky side of masking tape can be used to collect crawling immatures.

Diseases: Lone Star Ticks are the primary transmitter of human monocytic ehrlichiosis and southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI). They also may transmit tularemia and Q-fever.

How Can I Prevent Tick Bites?

Here are some preventative measures that can be taken to reduce the chance of humans and pets being bitten by a harmful tick while outdoors:

Humans

• Wear long sleeves and long pants

• Wear light colored clothing to make it easier to find ticks

• Tuck your shirt into your pants and your pants into your socks and boots

• Always know when and where to expect to encounter ticks (Blacklegged/deer Ticks are found in the woods; American Dog Ticks are found near roadsides, grassy areas, and meadows; Lone Star Ticks are found near roadsides, grassy areas, and meadows primarily in southern Ohio)

• Use repellents according to the label

• Check yourself, family, and pets regularly and remove ticks immediately

• Avoid grassy and overgrown areas by staying on designated paths

Pets

• Use anti-tick products on pets

• Ask your veterinarian about Lyme Disease shots for your pets in areas with Blacklegged Ticks

• Create a tick-safe zone in your backyard for pets to avoid allowing them to roam freely

• Keep animals on a leash during walks and inspect them for ticks afterwards

Tick Repellant

To use tick repellent properly follow these steps:

1. Purchase a repellent that contains the chemical permethrin

2. Apply the repellent to your boots and pants and allow to dry

3. When entering the field, tuck your pants into your boots to prevent ticks from accessing your body

Once the permethrin has dried, there is no odor and it should remain effective for several weeks before reapplication is needed.

Check out this printable brochure from the ODH on preventing tick bites and infections: Be Tick Smart

Tick Identification

Ticks can be submitted for species identification to the C. Wayne Ellett Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic (PPDC) at The Ohio State University. Information detailing how to submit a specimen can be obtained from the PPDC website, your local county extension office (OSU Mansfield Extension), or by contacting the PPDC directly via phone at (330) 263-3650 or email at ppdc@osu.edu.

How Do I Remove a Tick Properly?

If you encounter a tick on your, a family member's, or your pet's body, do not panic. Carefully remove the tick using tweezers, making sure to include the mouth parts. Monitor the health of the individual that has been bitten over the next 36-48 hours because transmission occurs during this time period. Check out this quick video detailing proper tick removal technique:

Most people bitten by a tick will not get a disease. Not all ticks are infected with diseases. Ticks that are infected usually have to be attached to the host for several hours to several days to transmit diseases. Prompt removal of an attached tick will significantly reduce the risk of infection.

What Is a Coyote?

The Eastern Coyote (Canis latrans) is the most widely distributed carnivore found in the western hemisphere including all 88 Ohio counties. Coyotes originated from the western United States, inhabiting desert and prairie habitat. However, due to deforestation and the extirpation of the Eastern Timber Wolf, their range has expanded exponentially over the course of the last century. Coyotes are known for their high level of intelligence and uncanny ability to adapt to their environment and thrive, especially in urban areas such as Chicago, New York City, Los Angeles, and even Cleveland. Coyotes have been documented in Ohio since 1919.

How Can I Correctly Identify a Coyote?

Coyotes are slender animals similar in appearance to medium-sized dogs, most closely resembling a German Shepherd. Because Coyotes and domesticated dogs are from the same family, Canidae, they share similar appearance characteristics. Coyotes can reach lengths of 28-29 inches with a tail length of 12-15 inches and weigh approximately 20-50 lbs, with males being larger than females. Coyotes have bushy tails tipped in black that hang at a 45 degree angle when on the move. This trait is distinct to Coyotes, unlike the wolf. Other field markings include a long, pointed snout, and pointed, erect ears. The long hairs on the back are tipped with black and run the length of the back through the tip of the tail, creating a dark band. Several color variations exist, including tan, reddish, brown, and black.

Where Do Coyotes Live?

Coyotes can be found in a wide variety of habitats ranging from urban to rural, including grasslands, brush, and forests. Adult coyotes normally excavate one or more dens in the soil, sometimes by expanding the burrows of other animals. They usually choose sites where human activity is minimal. However, their presence in urban and suburban environments is increasing, and substantial populations exist in many large cities and suburbs in Ohio, including Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati. They are considered to be one of the most highly intelligent and adaptable carnivores. In urban environments, Coyotes can create makeshift dens out of areas such as storm drains, culverts, holes dug in vacant lots and parks, underneath storage sheds, or just about any dark, dry place.

When Are Coyotes Active?

The Coyote is primarily a nocturnal animal (most active at night). However, they can be observed during the day when not threatened by human activity. Coyotes are often encountered alone, but will frequently hunt in non-family pairs or large groups, which may range over several square miles. Coyotes are omnivores - like many other animals, they are opportunistic, feeding on a variety of items including small mammals such as voles, shrews, moles, rabbits, etc. as well as vegetables, nuts, and even carrion. Coyotes are not pack animals like wolves. Family groups do exist and typically consist of two breeding adults, juveniles, and newborn pups.

What Is the Role of Coyotes in the RCPD?

Coyotes are part of our park system's natural resources. Over the past two decades, they have become a normal part of the wildlife populations of the park district, as well as suburbs, surrounding rural areas, and other natural areas throughout northcentral Ohio.

Although non-native, Coyotes have become a staple top-level predator in Ohio's ecosystem. Coyotes are a natural control that keeps small mammal populations in check. They also prey on growing populations of feral cats, feral dogs and Canada Geese that can cause damage to natural resources. Today, the Coyote is the largest mammal to function as a predator in this region. Although Coyotes are predators, they are also opportunistic feeders and shift their diets to take advantage of the most available prey. Coyote diets are made up of small mammals, mostly mice and other rodents, rabbits, raccoons, ground-nesting waterfowl/songbirds and their eggs, carrion, reptiles, amphibians, and berries/fruits.

What Should I Do if I Encounter a Coyote?

Simply seeing a Coyote is normally not a cause for concern. Coyotes may frequent residential areas out of curiosity or as part of their normal travel routines. Many people have never seen a Coyote, so unless there is cause for concern, enjoy the rare opportunity and watch what they are doing.

If you witness what appears to be an injured Coyote or have had a concerning encounter please contact the Richland County Wildlife Officer at (419) 429-8392.

Coyote Concerns

More often than not, Coyotes are wary of human activity and keep their distance. It is important that this relationship be maintained. Do not give Coyotes a reason to get comfortable near people or pets. “Keep Wildlife Wild” by eliminating food sources (pet food, garbage, etc.) and stopping intentional wildlife feeding. Pet food and water should be kept indoors to avoid attracting Coyotes to your yard. Small pets that are roaming freely can resemble prey to Coyotes. Experts recommend not to leave small pets unattended. Best practices recommended to keep pets safe are to keep cats indoors and pets on leashes within your sight.

The Coyote mating period is from February through early March. Pups will be born from mid-April through May. During this period, Coyotes, like most other animals, can act aggressive toward perceived threats to the pregnant female and/or newborn pups. Coyotes are protective parents, and defend their young just as humans do. Domestic dogs may trigger Coyote defense behavior even if they are with their owner and showing no signs of aggression towards an encountered Coyote.

Humans encountering Coyotes rarely trigger an aggressive response that results in physical contact. On the very rare chance that a Coyote does approach you directly, appears to be intentionally entering your line of travel, or begins to follow you, as with most predatory animal encounters, it is imperative you DO NOT turn and run because it may trigger a predatory/aggressive response from the Coyote.

Understand that the Coyote likely views you, or your pet, as a threat, or it may be a sick animal. If you have a pet on a leash, make sure it is under control. Do not release it or command it to attack the Coyote. Walk slowly backward so that you do not turn your back on the Coyote. Back-tracking on the route you took will often lead you out of a den area or away from protected pups. If you are on horseback, slowly leave the area by retracing your route.

If you feel threatened, try to frighten the Coyote away by shouting in a deep voice, waving your arms, throwing objects at the animal, and looking it directly in the eyes to make yourself seem large and menacing. Stand up if you are seated. If you are wearing a coat or vest, spread it open like a cape so that you appear larger. Carrying a whistle with you can aid in frightening a Coyote and summoning others to assist you.

Report any incidents of aggressive Coyotes to local authorities, including your local animal control agency.

Although most Coyotes are healthy, they can carry raccoon- and canine-strain rabies. Infected animals in the latter stages of the disease will act aggressively towards humans perceived as threats. If someone is bitten or scratched by a Coyote, wash the affected area thoroughly with soap and water and seek immediate medical attention. Because rabies infections in humans are nearly always fatal, medical authorities recommend post-exposure immunization whenever a person comes into direct contact with a wild Coyote during a conflict. If a dog is bitten, the owner will need to ensure a rabies booster is administered immediately. In either of these cases, report the incident to local authorities (Richland County Sheriff's Office).

If Coyotes approach without fear, become aggressive, or are taking pets from yards, then further action may be needed. Within the Richland County Park District, call staff at (419) 884-3764. On private property or elsewhere, contact the local police department or animal control warden.

• Do not feed Coyotes

• Do not let pets run loose

• Never run from a Coyote

• Repellents or fencing may help

• Do not create conflict where it does not exist

• Report aggressive, fearless Coyotes immediately

You can also find urban Coyote information from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

What Is a Bobcat?

Bobcats (Lynx rufus) are a small, predatory wild cat species native to Ohio, and one of seven wild cat species found in North America. Bobcats belong to the same family as domesticated cats, Felidae. Prior to the settlement of Ohio during the 19th century, Bobcats once roamed freely without persecution, but similar to other large predatory animals present in Ohio during this time period, they were aggressively hunted and extirpated from the state in the 1850's. In the 1970's, Bobcats began making a comeback in Ohio with scattered reports and sightings. In 1974, the Bobcat was designated as an endangered species. Since then, more and more sightings have been reported, and in 2012, Bobcats were delisted from endangered to threatened species in Ohio. Today, they are no longer listed as threatened, but are still considered a protected species with no designated hunting or trapping season.

How Can I Properly Identify a Bobcat?

Bobcats are small predators that are nearly double the size of a domestic cat. They have short, dense, soft fur that is variable, but typically includes colors ranging from light gray to yellowish/buff brown with black spots on the upper or dorsal portion of the body. The underside or ventral side and inside of the legs of the Bobcat are usually whitish with dark black spots or bars. Although much smaller than but otherwise similar in appearance to the Lynx, Bobcats have a distinct short tail that is black on top and white underneath. Bobcats have pointed, erect ears that are tipped in black. The backs of the ears are spotted in white.

Where Do Bobcats Live?

Bobcats are extremely territorial, with most females being intolerant of other females in their territorial range. Males tend to be more accepting of other males in their territories. Bobcats can inhabit a variety of habitats, including grassland, forest, wetland, desert, and even suburban areas. Females create dens in dead trees, tree cavities, cacti, holes in the ground, or rock formations to care for juveniles and newborn kittens.

When Are Bobcats Active?

Bobcats are crepuscular creatures (most active during early morning and evening hours). Seldom seen due to their elusive nature, Bobcats are solitary, carnivorous ambush predators that have an affinity for rabbits and snowshoe hares, although they do have a wide diet consisting of an array of options such as insects, reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds, and other small mammals.

What Is the Role of Bobcats in the RCPD?

Bobcats are becoming increasingly more common throughout Ohio and even Richland County, and are part of our park system's natural resources. Over the past two decades, they have become a more normal part of the wildlife populations of the park district, as well as suburbs, surrounding rural areas, and other natural areas throughout northcentral Ohio.

Since numbers have rebounded, Bobcats have become a staple top-level predator in Ohio's ecosystem. Bobcats are a natural control that keeps small mammal populations in check. Today, the Bobcat is one of a handful of mammals to function as a predator in this region. Although Bobcats are predators, they are also opportunistic feeders like most other animals and shift their diets to take advantage of the most available prey. Bobcat diets are made up of mammals, mostly small mice and other rodents, rabbits, raccoons, ground nesting waterfowl/songbirds and their eggs, carrion, reptiles, and amphibians.

What Should I Do if I Encounter a Bobcat?

Simply seeing a Bobcat is normally not a cause for concern. Bobcats may frequent residential areas out of curiosity or as part of their normal travel routines. However, they are typically elusive and avoid people. Most people have never seen a Bobcat, so unless there is cause for concern, enjoy the rare opportunity and watch what they are doing.

If you witness what appears to be an injured Bobcat or have had a concerning encounter please contact the Richland County Wildlife Officer at (419) 429-8392.